Etosha, Northern Namibia

Reconnecting with ancestral territory

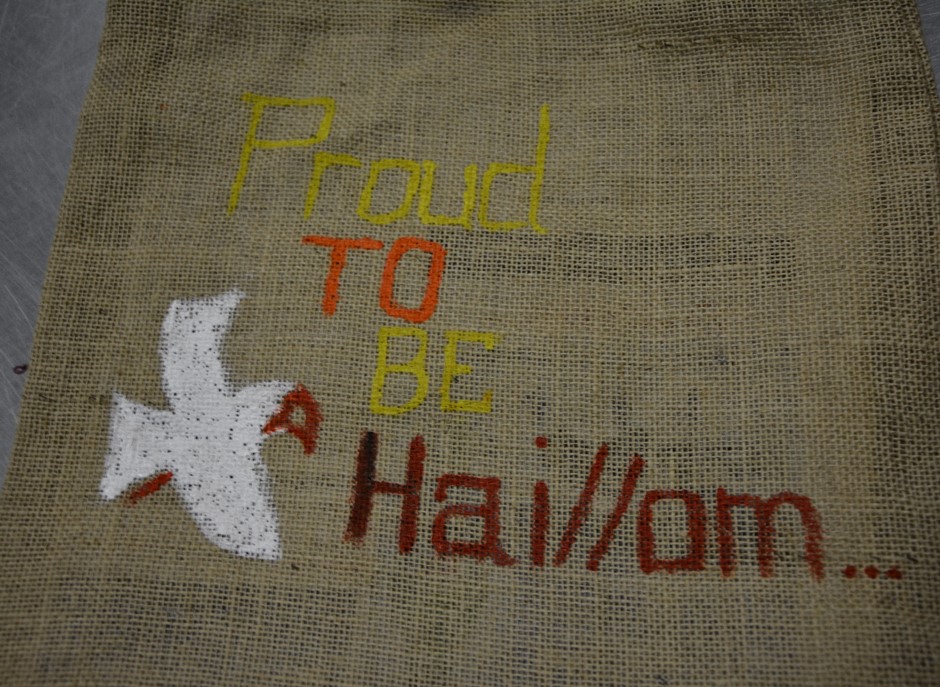

The Hai||om are one of several San groups in Northern Namibia, counting about 10,000 members. Following colonial land dispossession, the group finds itself today widely dispersed – some Hai||om live on government resettlement farms, others in informal settlements around small towns, still others on agricultural estates earning their living as farm hands. In contrast to other groups in the country, since Namibia’s independence in 1990, they have not been granted access to communal lands.

Their ancestral lands are situated in what is known today as Etosha National Park, a tourist destination of great importance to the national economy. The Hai||om were evicted from their homeland in the 1950s, at a time when the dominant nature conservation paradigm dictated that protected areas should be free of people – even of the ones who had cared for these lands since time immemorial and guaranteed its continuing existence. This “fortress conservation” model based on the exclusion of local people has lately been the focus of widespread criticism. Increasingly, there is an appreciation of indigenous peoples as stewards of their lands as well as a growing acknowledgement of their valuable contributions to biodiversity conservation, ideally going hand in hand with land security.

Jan Tsumib is one of the few remaining Hai||om elders who was born in Etosha and who had spent his childhood there. When we met him, he expressed a strong sense of urgency to stop the erosion of his people’s culture and historical memory. He yearned for an opportunity to transmit his knowledge to the younger generation. Together we envisioned taking a group of Hai||om youth to Etosha. OrigiNations then supported him and his community to organise and implement a 10-day immersion workshop at the ancestral sites within the national park.

This pilot workshop, which was a direct response to Jan Tsumib’s dream, took place at the facilities of the Environmental Education Centre of Etosha National Park, between the 8th and the 17th of August of 2018. It was the first time a group of Hai||om had used the facilities in this way – lodging, exploring, learning and working together in spaces usually reserved for outside school classes or social groups. Gaining permission to do the workshop within Etosha was made possible by the high level of esteem that Jan Tsumib held among the park employees, who had benefited from his immense knowledge of the Etosha ecosystem during the 30 years he had worked there as a ranger. They had learned from him how to survive in the bush and some claimed he had saved their lives on several occasions. As a clear acknowledgement to the enormous contribution he had made to the conservation of the protected area, these old colleagues, who had over time become park officers, moved heaven and earth to make Jan’s wish come true.

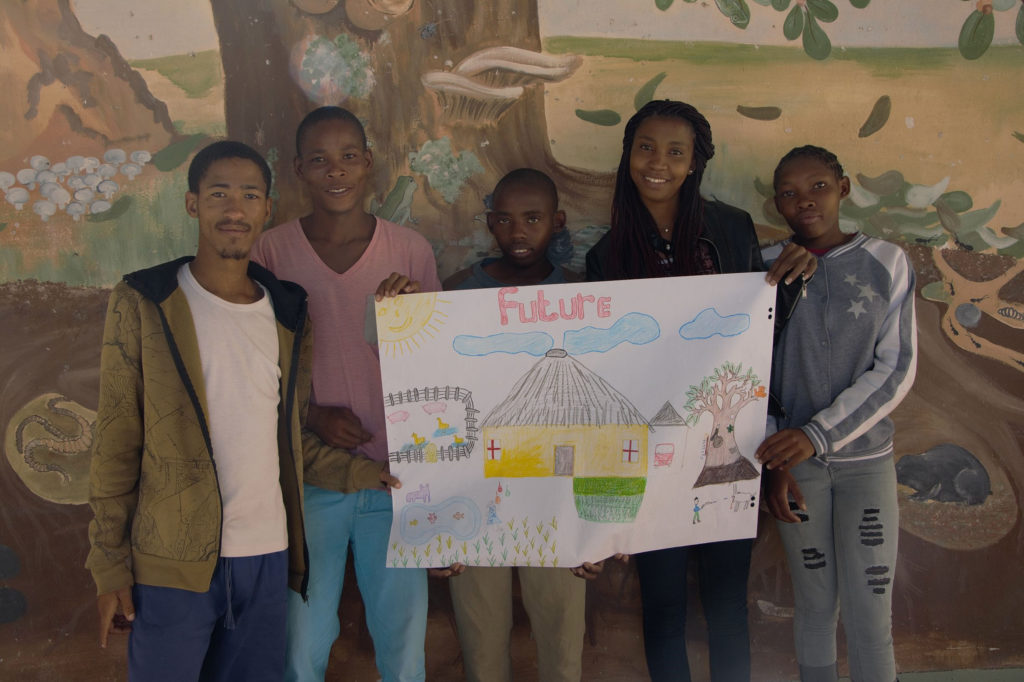

Staying in the park for an extended period of time enabled Jan Tsumib and two other elders to share their knowledge, skills, values, and memories with the group of young Hai||om who attended the workshop. They revealed to them the secrets of this biodiversity-rich landscape and told them many stories of their ancestors at the very places where the events had occurred. Together, they visited the life-giving waterholes where their forebears had settled and also the places where they now rest. There were lessons on nutritional and medicinal plants, training in audiovisual documentation of knowledge, storytelling and dances around the campfire, and a good deal of discussions and creative exercises.

Many of the young had never been to Etosha before and the days they spent there learning and carrying out cultural activities in this space carried great symbolic value, it was in a way a form of re-appropriation of the ancestral homeland. Furthermore, these days offered the participants an opportunity to start generating their own strategies and proposals for the best ways to protect and advance their cultural heritage. The last two days of the workshop took place at Ondera, a government resettlement farm where Jan Tsumib and most of the other workshop attendees live today. Here, the young participants informed their peers and the larger community about their experience at Etosha, sharing with them their newly acquired insights and skills. The event closed on a celebratory note, with community elders and youth joining in a day of storytelling, song and dance.

Statements by the workshop participants:

Jan Tsumib (elder): “We have lost our treasure that is Etosha. Having lost our land made us lose our language, culture, knowledge, and heritage. In the past, people practiced dances and songs, today young people play the radio and listen to music made by others. We are trying to live the lives of others today. We as elders don’t want our culture to die out – that is why we are here teaching the young people.”

Memsie Hanes, 23: “Many of us did not have the chance to grow up with our grandparents. Today, many young people drink or take drugs because they do not know about their culture. I feel very thankful to the elders who have left their homes and families to accompany me during my first time in Etosha and teach me so much.”

Jacob Gaiseb, 22: “During this week, we have recuperated our background and we have strengthened ourselves. We learned many things that we did not know before. I admire the life of the Haiǁom in the bush in the past because they were free. I want to continue to learn from the elders before they leave and gather their knowledge and information.”

Nani Gamamus, 18: “I feel that my grandmother’s life was better than mine. She knew more than me. She could just not read or write, but she knew so much more.”

Read more of their statements here.

_____________________________

Background

- You can find the report of the workshop here.

- Watch a 3-minute video of the workshop.

- The website of the Xoms ǀOmis project with materials on Haiǁom culture in Etosha, by anthropologist Ute Dieckmann: https://www.xoms-omis.org/

- Legal Assistence Center (2020): “Neither Here nor There – Indigeneity, marginalisation and land rights in post-independence Namibia”. Edited by Willem Odendaal and Wolfgang Werner.